Columbus Monthly: Columbus Composer Helps Us Learn To Hear

Columbus-based composer and pianist Brian Harnetty lived in Berea, Kentucky, in 2006, working to complete a fellowship at Berea College. Each morning, he headed to a basement library on campus and immersed himself in one of the world's most significant sound archives documenting Appalachian history and culture. In long rows of cataloged stacks are thousands of recordings: oral histories, old radio shows, field recordings from people's homes, others from inside the region's many churches. The sound archives—stored in a mix of mediums—include open reels, cassettes, and even some 78s. With nearly 85 years' worth of material, it would take someone a lifetime to listen to everything. Harnetty had only a month.

He'd sit, headphones wrapped around his head to cancel out the world around him, listening to samples, eight hours a day, days on end. The recordings he selected were, by default, mostly random. Some he found searching the catalog with keywords like "winter" or "night." Others were suggested by archivists and librarians during coffee breaks. Then one day, Harnetty heard a voice—raspy and boisterous, an emotive contralto unaccompanied by instrumentation. It was Addie Graham, a singer of traditional ballads and hymns, many originating from the British Isles. The recordings were made in the 1970s. Graham was born in the late 1890s in eastern Kentucky and sang in obscurity until her early 80s, when she began performing at regional musical festivals. It was the rough cuts of these recordings, the lulls between songs when Graham bantered with others in the studio or laughed with abandon in a high-pitched peal, that Harnetty listened to over and over again. "You could hear how alive she is," Harnetty explains in a recent interview at his home studio in Clintonville. "She is so full of life."

The weekend after first listening to the Graham archives at Berea, Harnetty attended a party in nearby Whitesburg, Kentucky, and talked about the impression Graham had made on him. "Oh, yeah, that's my great-grandmother," a woman at the party, Amelia Kirby, told him, and proceeded to introduce the young composer to her father, Addie Graham's grandson, Rich Kirby, who has worked to keep his grandmother's music alive. This unexpected and brief connection with the descendants associated so intimately with a sound archive already chosen by Harnetty changed many things for the young composer. Harnetty had been using samples from sound archives in his works without seeking direct permission from the musicians or singers, or ever meeting someone with a direct connection to a recording. This serendipitous encounter altered not only how he now thinks about sound archives, but how he approaches his work as a composer. Sound archives are not sterile, dead things, he came to understand. They have their own lives. They are connected to living human beings.

Harnetty's 2007 album, American Winter, represented the first expression of this new vision. The first track opens with Graham's infectious banter: She's clearing her throat, asking where to stand and, at one point, begins to talk about Florida. The effect is a rare and unexpected intimacy. Graham then begins, with uncommon force and authority, to belt out a soulful ballad about birds singing in the winter ... on every leaf and vine. The effect, for the listener, is a bit like eavesdropping, though more intimate. We have been invited. We can hear Harnetty listening along, adding his own layer of meaning to this decades-old recording: dissonant piano chords and softly rung bells. "Haunting" might be a fitting way to describe the song's effect, but it would be the wrong word—a two-bit cliché, and the effect is something else entirely: an act of transport to the past without the schmaltzy feel of nostalgia.

Harnetty's second major work, 2009's Silent City, is described as an "otherworldly album that demands—and deserves—undivided attention in a darkened room with some good headphones" by a music critic at Paste magazine. The album revolves around a myth: the imagined small town. It still operates largely as an abstraction. Harnetty is moving toward something different, even if he doesn't yet know what exactly that something is.

Shawnee, Ohio, population 655, was founded in 1872 and once was the largest town in Perry County. Harnetty's maternal ancestors arrived in this village the year of its founding, part of a migration of Welsh miners seeking work in the booming coal fields of the region. His grandfather, Mordecai Williams, grew up here, played saxophone and piano at the high school, then left, after graduating in 1925. Harnetty first visited Shawnee's Main Street, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, in 2010, after he had started working with Marina Peterson, a performance cellist and an associate professor in the School of Interdisciplinary Arts at Ohio University. Working with Peterson, an anthropologist who has spent her career integrating the discipline with sound studies, Harnetty completed a doctorate in interdisciplinary arts as he developed a new approach to his work as a composer and began merging sounds archives with ethnography.

Instead of an imagined small town, he spent more than five years coming back, again and again, to Shawnee, trying to understand his personal connection to this place. His performance here is the culmination of those years of "deeply hanging out," as Harnetty puts it, in a real place, with real people. "This whole new process means that I can't detach myself from the piece," Harnetty says. "It's not an abstract thing. It's a very concrete world, and there are people connected to the archives, and I have a responsibility to do a piece that I believe in, something that offers respect and dignity to the people I have been sampling."

Harnetty debuted Shawnee, Ohio, a composition named after the town, with performances at the Wexner Center for the Arts, which co-commissioned the piece, in October. But it is here, in Shawnee's old opera house, built in 1907 and known today as Tecumseh Commons, that the composer has most wanted to perform.

During a potluck dinner before the show in the downstairs lobby, Skip Ricketts, who owns the building, takes a group to the upstairs theater. Standing in the dusty and cavernous space, Ricketts explains how he came to own the tallest privately owned building in Perry County (only the county courthouse is taller) and spent decades trying to revive it. He was running a diner in Shawnee, back in the summer of 1976. Two guys came into the diner for a cup of coffee. They told him their plan to tear the 75-foot-tall building down, only to salvage the building's massive steel I-beams. "For them, the only value in this building was some steel," Ricketts says. He asked the two men how much they were paying. $500. Ricketts immediately went to the owner of the building and talked him into selling it to him for $500, even though he didn't have the money to buy it. He borrowed the cash from his father. "For 20 years, it rained into the building after a fire next door jumped to the roof and put holes in the ceiling," Ricketts says, pointing up to the ceiling. "It's a testament to the structure that it really didn't hurt it." There has been the occasional grant, bake sale, concert, and for 30 years, a basketball tournament to raise money. "A million dollars in here wouldn't even go very far," Ricketts admits.

The walls are bare to the lath. In a corner, a sign says: "TO-NIGHT BASKET-Ball DANCING."

A dusty piano, its guts open, has keys like broken teeth, blackened and crooked. There are signs of progress: new wooden stairs up the three flights from the downstairs lobby; drywall on the right wall of the theater, up to the ceiling over the thin lath—wood planks that run horizontally like music staff. But the stage curtain—Ricketts tells us he suspects it's made of asbestos—has not been moved. The opera house was a place once full of life, from its first event in 1907, a basketball game, to the site of high school graduations and class plays.

It has also been a 210-seat movie theater, with one of the first sound projectors in the state, and after the shows, people would move the chairs and make room for a band, dancing into the night. When Ricketts was growing up in Shawnee, he watched picture shows in the theater every weekend. There are no picture shows in Shawnee anymore.

Downstairs the potluck is ending. A gaggle of kids roam about eating cookies. The adults grab cans of beer and wine from a makeshift bar near a small kitchen, before settling in a semicircle in front of a makeshift stage. A video projector in the back of the room is aimed at a blank white wall. It's too dusty and dangerous to hold concerts with a full audience upstairs, although earlier in the day, Harnetty recorded a session of Shawnee, Ohio upstairs with the eight-person orchestra, which includes flute, saxophone, bass clarinet, banjo, cello and viola, along with Harnetty on piano and electronics.

Harnetty is dressed casually in a flannel shirt and jeans. Tall and bespectacled, he has an imposing presence, yet he speaks reservedly and with complete sincerity when he begins his introduction to the crowd of about 60 or so. Within moments, his 8-year-old son walks up, puts his arm around him, trying to get his attention. "I need to talk right now," Harnetty says, gently. "This is my son Henry; he's going to be really good in the front row." But Henry runs off with a group of kids who play tag outside in a small garden park next to the theater, where a bronze statue of a coal miner stands watch.

Harnetty gives a brief overview of the performance, explaining the score's structure and origins—11 portraits of actual people, told through a montage of archival videos, photos and sound recordings. Many of the tracks focus on Shawnee, stitched together by Harnetty's original score. Some of the videos were found during the many interviews he conducted with people in the region, including a man from Murray City who handed him a video cassette tape after he met him and said: "Either there's some 1920s and 1930s coal-mining video on here, or it's stuff I taped from the History Channel." Harnetty was pleased to discover it was the former. The footage is spliced and cut within the work, mingling with new images and film of Shawnee today created by Harnetty. "The past and the present, sometimes they get a little mixed up," he says, as the lights go down and the performance begins.

It would be impossible to narrate the hour-long performance—it flits and lingers, shifts and cuts within a montage of tragic, celebratory and everyday events: the state's worst mine fire in 1930 at the Sunday Creek Coal Company, in which more than 82 men died, alongside footage of activists singing a protest song at a demonstration against fracking; a boy delivering papers; a murder ballad from the town of Gore, Ohio; a parade of musicians and young children riding bikes down a vibrant Main Street. It is an impressionistic tour de force through this region's past and present, and the lack of any systemization is, in fact, its greatest strength. History rarely has a clean narrative thread—and as it is often told, glosses over the social life of people and place. Harnetty avoids such traps, letting the people of this region, whom he has spent years listening to, speak instead. In doing so, he makes no narrative demands for a coherent storyline: The collage of images and archives conveys instead, and with admirable fidelity, a sense of this place, the struggle of its people and a reverence for the resilience and hope still found here. One comes away wanting all of history to be accompanied by a live score.

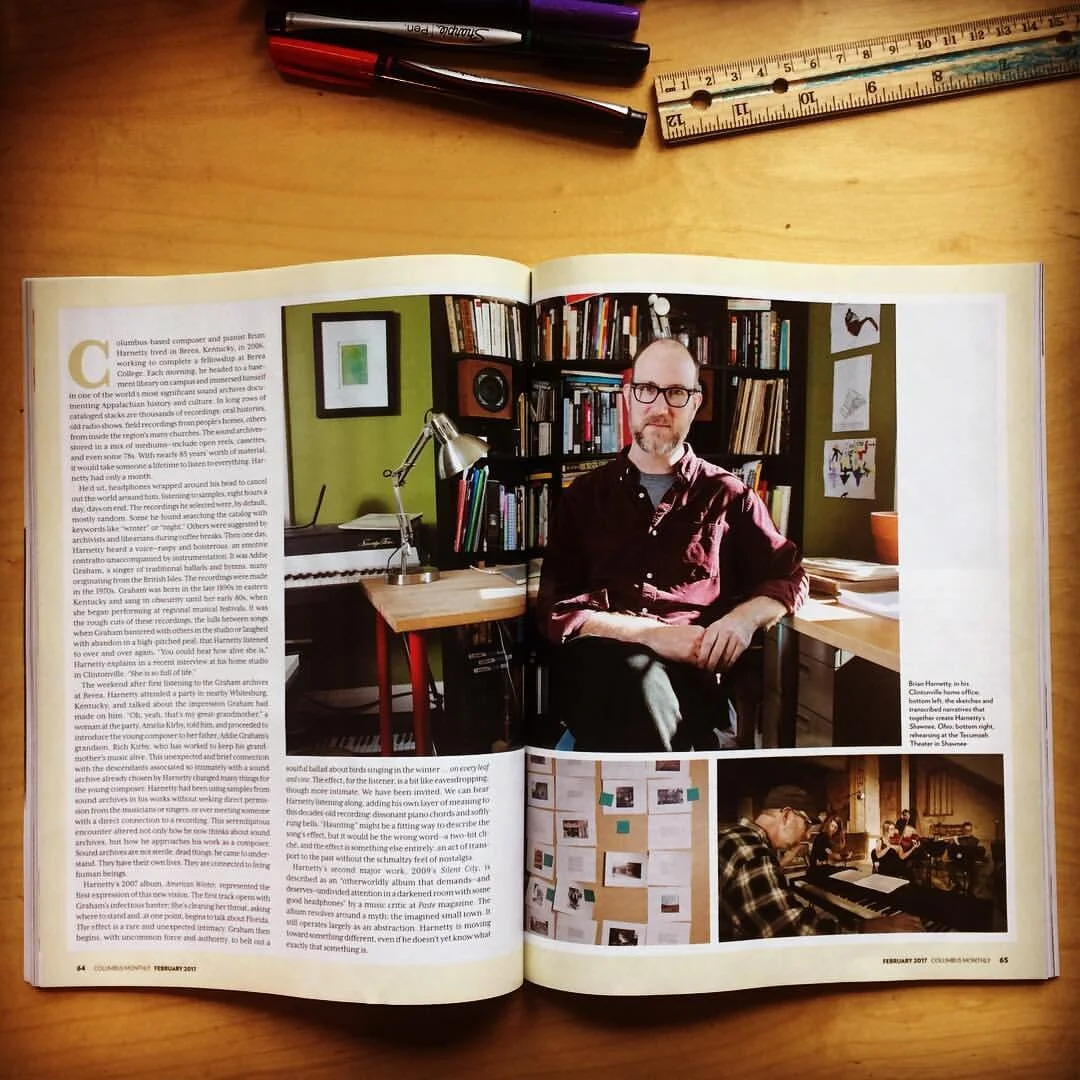

A few weeks after the Shawnee performance, I drive to Harnetty's home studio in Clintonville. When he opens the front door, his dog, Iggy, bounds out. As we sit in his living room for the interview, Iggy gnaws with great vigor on an enormous bone at Harnetty's feet. Surprisingly, considering the composer has spent so many years talking to veritable strangers in his field research for his latest project, Harnetty's natural state is reclusiveness. "I have to psyche myself to go talk to people," he says. "In the classical world, there's a lot of hiding out in the studio, in the practice rooms, and those things are so crucial to getting technique down. But you also have to live as a citizen and a human that interacts with other people. It is the only way to bring people into a relationship with the music."

Harnetty was born in 1973. He grew up in Westerville, and although neither of his parents were musicians, music ran through the family on his mother's side. He began taking piano lessons when he was about 6, and throughout his training, he often thought of the dreams his grandfather, Mordecai Williams from Shawnee, most likely gave up as the Depression limited his options—limits Harnetty has not himself faced.

In 1998, Harnetty moved to England. He earned a coveted spot at the Royal Academy of Music in London to study under Michael Finnissy, one of the most influential British composers of his generation. Finnissy, an experimental composer, samples folk music, sometimes hundreds of songs at a time, splicing them into a chaotic collage and creating a kind of musical commentary on how we understand what is rural and what is folk life. Finnissy's compositions operate firmly in the world of notation and classical music, and as such, operate as abstractions. "He was the first person with intelligence and authority in my life that believed in me," Harnetty says.

By 2000, Harnetty had completed his master's degree in music composition at the academy and returned to Ohio, a move encouraged by Finnissy. "He thought there was something here I really needed to investigate, and some questions I needed to answer," Harnetty says. But the young composer drifted. He waited tables at The Monk in Bexley. He became involved in environmental issues. He slowly unwound from the intensity of the Royal Academy, but the inspiration his mentor instructed him to find in his hometown eluded him. He moved to San Francisco and into a three-month residency at an artist's colony. He was the only composer among them. There were visual artists, sound artists and poets. He experimented with sampling and sound archives. A new world—outside of classical music—opened.

While Harnetty still considers Finnissy his primary influence, other composers inform his work, including experimental composers: John Cage, Morton Feldman, Frederic Rzewski, Steve Reich and Pauline Oliveros. "I was always interested in the political aspect of a lot of the composers who dealt with contemporary or political issues. All those things excited me. I wanted to find a way to combine those things into my work."

With Shawnee, Ohio Harnetty has transformed his quiet practice of listening into a novel new form of storytelling. Performance cellist Peterson praises Shawnee, Ohio for how it raised important contemporary questions. "How do we listen to a region? How do we listen to cycles of energy and economics? It was so powerful to see how this process of engagement manifested itself in his work," she says. "Brian is taking seriously human sound—the sound of coal, for instance. It's material, and it has a human angle, and he's taking on questions of political economy, but through sound."

––Mya Frazier, February, 2017